One ER Doc’s Journey Through the Pandemic— and the Health Care System

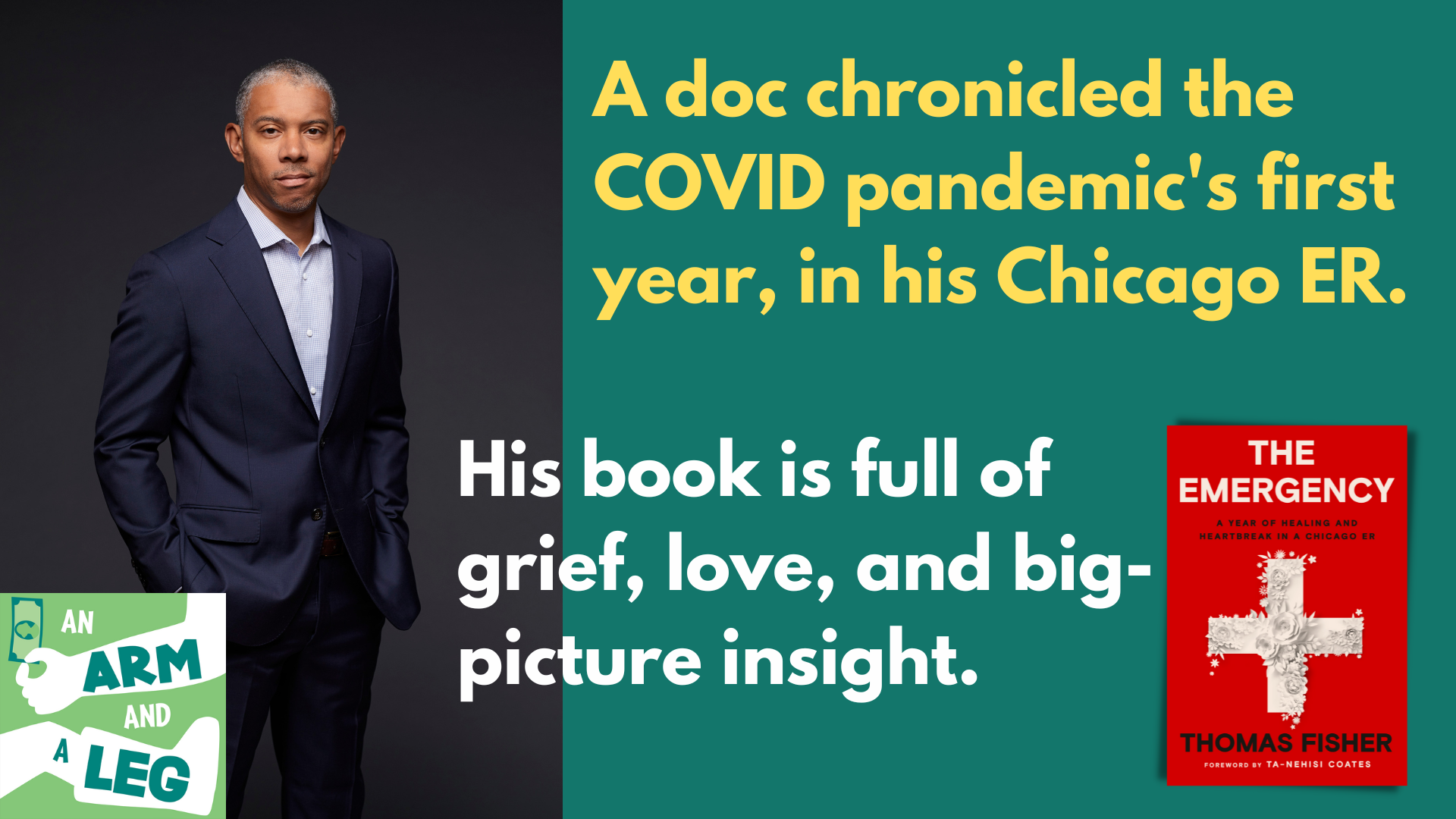

Thomas Fisher is an emergency room doc in Chicago. His book, The Emergency, is an up-close chronicle of the COVID pandemic’s first year in his South Side ER.

It also zooms out to tell the story of his journey as a doctor: How his upbringing on the South Side fueled his desire to become a doctor. And how the realities and inequities of American health care limited his ability to help.

He details how the failures of the American health care system, and the racial inequities it perpetuates , leave health care workers with a profound sense of moral injury.

“Over time, when you have this conflict between what you can do and what you’re supposed to do, what you wish you could do, what you’re trained to do, that creates a moral conundrum. It also leads a lot of people to leave the profession.”

For a time, Fisher himself stepped away from practicing medicine. The journey took him to the executive suite but ultimately landed him back in the ER, where he started.

On the street outside the hospital where Fisher works, he sits down with host Dan Weissmann to discuss the book and his search for meaning in the daily sprint of life in the ER.

Subscribe to our newsletter, First Aid Kit.

Send your stories and questions: https://armandalegshow.com/contact/ or call 724 ARM-N-LEG

And of course we’d love for you to support this show.

Dan: Hey there—

A few months ago, I read a book called “The Emergency” — by Thomas Fisher. He’s an ER doc, and this is his chronicle of the COVID pandemic’s first year.

And among other things, it is full of piercing descriptions of what he and others call moral injury. That’s when there’s deep conflict between what you feel you should do and what your job tells you you have to do.

Even when that’s something as simple as helping a patient get a pillow or allow them a visitor— or not. He writes that when he failed to help patients this way, he’d avoid their rooms, out of shame.

Here he is, narrating the audiobook:

Thomas Fisher: I’d close the door and try to forget. No matter what I said, they interpreted my inability to deliver as mistreatment. And while my avoidance protected me from feeling like a failure, it added to their perception of institutional neglect. They’re right. Their anger and sadness are justified and their assessment of my role is accurate.

I am a perpetuator of the system’s mistreatment and I am also a casualty trying to do the best I can with what I have.

Dan: This phenomenon, moral injury, lots of health care workers describe it. But not in this kind of detail, at this length.

He describes a shift where he’s got three minutes with each patient— which fulfills a mandate that patients get seen by a doctor as soon as possible, even if those three minutes aren’t enough to actually help them. Often they’re just a prelude to a long wait for actual treatment.

He describes waking up the morning after a shift, haunted.

Thomas Fisher: Now I remember the time I couldn’t remove a bullet or relieve cancer pain. When my patients implored me to. I knew they required more, but I did only what I could. Was it enough? Acquiescing to suffering, wounds something deep inside me. I know it. I just don’t know what I can do about it.

Dan: I read the emergency this spring and was like, “I want to meet this guy.” And: he’s right here in Chicago, where I live, writing about places I know.

I meet up with Thomas Fisher at a noisy intersection in the middle of the University of Chicago Medical Center’s complex on the South Side, where he practices.

Dr. Fisher.

Thomas Fisher: Yeah.

Dan: Hi, how are you? Good to meet you. Good, good. How are you? Good.

Thomas Fisher: Good.

Dan: Of course moral injury was one thing we talked about…

Thomas Fisher: over time, when you have this conflict between what you can do and what you’re supposed to do, what you wish you could do, what you’re trained to do, um, that creates a moral conundrum.

That, you know, leads people to a lot of different conclusions, but it also leads a lot of people to leave the profession.

Dan: Actually, it led him to leave the profession, at least for a couple of years. And he’s never returned to it full time. Thomas Fisher spent years trying to change the system itself from within, became an executive— while also putting in a shift or two a week in the ER for most of those years.

And he concluded: the system’s too big for him to change, even with allies. Bigger than health care itself. He left the c suite, started putting in more shifts, and started writing the book that became “The Emergency.”

His story is about learning how to carry on in the face of something intolerable.

And for everybody who bumps up against big, crushing systems — like me, for instance, and probably you — that’s a lesson worth studying.

This is An Arm and a Leg— a show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter, and I like a challenge. So my job on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life and bring you something entertaining, empowering and useful.

And this story, I think it’s a pretty good test.

Most of “The Emergency” toggles between two modes. Pretty much every other chapter chronicles a day in his emergency room. Each of the alternating chapters takes the form of a letter to one person he encountered in the day he’s just described. Usually a patient, sometimes a colleague.

The first of those letters is addressed to Janet, a middle aged woman who shows up with a gunshot wound to the shin. He gets three minutes with her. It’s March 2020. All she wants is to see her mom, who’s in the waiting room, but it’s COVID, no visitors. He has to suggest FaceTime instead.

The letter to Janet tells his origin story— he’s explaining: I’m your neighbor, you’re my people.

We learn about his parents — how they came to raise him on Chicago’s South Side, in Hyde Park, an integrated island in a segregated city.

His dad was a doctor, practiced at a hospital in the neighborhood. His mom was a school social worker who made sure that Thomas and his sister knew that they were part of a community. She brought them to church, even though she was an atheist.

He writes,

“We had a Black dentist, a Black orthodontist, a Black pediatrician, a Black pharmacist; our postman was Black, our fishmonger was Black, and so was the man at the shoe repair shop. None of this was accidental.”

That is, it was intended as a lesson. His family wanted to make sure he saw Black people in positions of responsibility and authority.

Another lesson his family taught: That unlike white kids, he didn’t have what he calls the “luxury of mediocrity.” Or of having less than impeccable manners.

That’s one origin story— the world his family raised him in, and his formal education.

And then there’s the story of three murders that constituted a different kind of education. When he was nine years old, getting interested in sports, a local high school basketball star named Ben Wilson was killed.

Thomas Fisher: He was a middle class black kid, and all of a sudden gone, right? Went from being the number one prospect in the country, to being a historical footnote. And I think that that brought very close to us all that none of us are really safe.

Dan: A few years later, even closer to home, Thomas Fisher’s mentor on the high school track team was shot outside of school. It was a second notice that a middle class upbringing — a commitment to being twice as good, to Black excellence — wasn’t enough protection.

Thomas Fisher: and then third was Robert Russ who was a Northwestern student and a traffic stop turned into the end of his life.

Robert Russ grew up in the Chicago area. He was about to graduate. Thomas Fisher, by that time back in town for medical school, saw a deeply familiar figure.

Thomas Fisher: Another one of these middle class black men who was culled.

Dan: Thomas Fisher concludes his letter to Janet saying: You and me, we’ve been shaped by the same place. We’re family. And that’s why, he writes: “Taking care of folks right here is my life’s work.”

So, what made him step away from it?

That’s right after this.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with Kaiser Health News. That’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health care in America. KHN is not affiliated with the giant health care outfit Kaiser Permanente. We’ll have more information about KHN at the end of this episode.

So, Thomas Fisher came to the University of Chicago’s emergency room to serve the community that shaped him. It was his life’s work. How’d he end up stepping away?

As Thomas Fisher began his career at the U of C, the hospital CEO was laying out a vision: Send more local patients elsewhere for routine care, so the hospital could focus its high-powered, expensive resources on the most complex cases.

In theory, that rationale sounds sensible. Lots of people do end up in ERs because they don’t have better alternatives for routine care.

In practice, that meant cuts to the emergency room, extending wait times, and sending more patients to often-distressed, under-resourced community hospitals for treatment instead of admitting them.

Even when some of those patients were clearly in an emergency. The Chicago Tribune published the story of a kid mauled by a dog, who waited hours to be seen, only to be sent away without getting stitched up.

A major medical association called it “dangerously close to patient dumping.”

The hospital’s strategy was openly aimed at keeping its own budget healthy: After all, focusing on complex cases often means serving people with private insurance, which changes the mix of who the hospital actually serves.

Thomas Fisher: institutions want to get paid the most for doing the same amount of work. And it’s private insurance that pays the most. And so. All of our healthcare institutions try to attract those with private insurance

now, if you take a step back and you know, the literature that describes how these jobs that provide this good paying insurance are also structured by racial cast, then it doesn’t require that a hospital say, look, we don’t want black folks.

You can just say, well, what we do want is better paying insurance people here, and it will have the same effect

Dan: After the 2008 financial crash, the plans to send local patients away accelerated.

Then management presented a new plan: cutting more space in the ER, and creating a new section for what Fisher says were called “patients of distinction.”

In the book he describes his distress, sleeplessness, nausea as he grappled with what the new plan would mean.

When we met, I asked him to read me this part:

Thomas Fisher: building a wall between the insured patients of distinction and the south side’s uninsured patients and patients with Medicare and Medicaid would effectively create one ER for white patients and another for black people.

The ed for black patients would be challenged to serve many more patients in a much smaller space, overcrowded and under resourced. The ed would become a site where people would wait an intolerably long time for care. If friends, childhood teachers, or my parents arrived with a medical emergency, they would end up on the wrong side of that wall.

I’d come to the university who care for the community that raised me. Now, instead I was enrolled in a plan to Flo brown versus board of education. In order to funnel precious healthcare resources to patients of distinction. I was to be the black cop restraining his neighbor, the black prosecutor convicting his brother, the black lender denying his sister’s mortgage.

Dan: He decided… he couldn’t do it. He wrote an email saying just what he thought, figuring a resignation letter would follow.

Thomas Fisher: Sometimes there is no middle you’re on one side or the other and you have to choose. And so while that choice may be hard and distance you from, you know, your previous hopes and goals, it’s also clear.

And sometimes those are easier choices to make.

Dan: He didn’t quit right away. His email got forwarded around. He got a call from the CEO, and he helped push through a plan that was at least a little less discriminatory.

And he started looking for a way out. Not just out of that job, but out of the profession entirely, at least at first.

And into a series of adventures— explorations — of other ways he might make a difference.

First stop, Washington, DC. As a White House fellow, he worked on regulations to implement the Affordable Care Act, which had just passed.

That was a one-year posting. Next it was time for a bigger commitment.

He moved back to Chicago and took a job as an insurance executive, hoping to change the system from within.

Thomas Fisher: I was still sort of trying on different sorts of leadership styles and trying to better understand, well, if it’s people, can I be one of those people?

One of those people who makes a difference.

Dan: He spent four years working his way up in a company that ran blue cross pans in several states— while working every Friday back at the ER he had left: keeping a hand in— keeping himself tied to his community and to the immediacy of caring for people.

He says he met lots of smart, hardworking people at the insurance company. Kindhearted even. But ultimately he decided: He couldn’t make the difference that he wanted to there.

So he joined a startup— became president of a company providing Medicaid managed care in Illinois.

Which was tough. Money was tighter than tight. To bring in new investors — which they needed, just to keep the lights on— they cut costs. They laid off the company’s patient navigators— basically case workers.

Thomas Fisher: these were the people who were our legs and ears in a community, which made us both unique and also made them particularly valuable. But they also weren’t quote unquote required.

Dan: The company didn’t get direct reimbursement for their work, any pay. Which is why their work made this company unique.

Thomas Fisher: our peers weren’t doing it. We were doing it cuz we thought it was right. And so. the way the decision was made, made sense.

And it was also the final straw in this disillusion meant

Dan: I always wondered why disillusioning was usually considered like a negative word. I was like, well, don’t we want to have fewer illusions?

Thomas Fisher: Yes. Let’s be clear about what we are dealing with.

Dan: About a year after the layoffs, he left the startup, started taking on more shifts at the ER, and started writing the book that became “The Emergency” — aiming to put what he had learned into perspective.

Thomas Fisher: in my youthful naivete, I’m like, well, if I’m in the room, I can make the difference. I know different. Now I know these systems are durable,

Dan: Not long after he started writing, the COVID pandemic came along and gave the book its structure.

The chapters set in the ER vividly illustrate the challenges, the distress, that flood his day.

The alternating chapters — the “letters” to patients and colleagues — zoom out to diagram the structures, the systems, that bring this misery flooding in, that limit his ability to help.

To Janet, wounded by gunshot, he writes about the violence that hangs over their shared community.

To Nicole, who waited for hours to see him for only a few minutes, he writes about how this ER got so jammed, so slow: Largely because there aren’t enough other places for people on the South Side to seek care.

Which isn’t an accident. Where people are wealthier, and whiter, and more likely to have private insurance, he writes, there are plenty of resources, and emergency rooms tend to move faster.

To another patient, a young man with kidney failure, who has been shot, he writes: You’re unlucky, and it’s not just you. Bad luck is not equitably distributed.

At the end of the book, he’s still looking. But he’s concluded that not only are the real problems bigger than him, they’re bigger than health care. It’s not a satisfying conclusion.

Thomas Fisher: One of the questions I often get asked is, okay, all right, you’ve got this story. What do we do now? And on the one hand it’s really, uh, somewhat flattering, like, oh, you want my opinion on this?

Here. I am describing the world as I see it. Now you want me to tell you which way to go and I’m, and, and it goes back to this like, well, how, how much. Persistence are we willing to show?

It took generations to build this. It’s gonna take generations to dismantle it. And there’s going to be a lot of setbacks along the way.

Dan: Which leaves a big question. What do we do in the meantime? In a way, I think that’s a primary question of this show.

Our health care system’s failures — its cruelties and inequities— are driven by big, powerful forces. They’re not going anywhere right now.

In the meantime may be a very long time.

So all of the strategies, everything that we talk about on this show, are aimed at the question: Given how bad things are, what can help us now? What can help us survive through this very long meantime.

And there, I think, Thomas Fisher has something for us. Because in addition to distress, there’s something else that comes through in the chapters set in the ER.

It’s partly the way Thomas Fisher describes monitoring himself, making sure he’s really doing everything he can. And it’s the way he shows himself talking to his patients, taking care with his language and his tone, to communicate solidarity, care, cultural competence, respect. He acknowledges when things aren’t right. He makes apologies.

An extended scene takes place outside the ER. A couple of weeks after George Floyd was murdered in Minnesota, at 4 a.m., a phalanx of cops are trying to coax a biploar young man, off his meds, into the E.R. They ask Thomas Fisher to take the lead. (p 124)

Thomas Fisher: Abra. I’m Dr. Fisher. I spoke to your dad. He told me what’s going on.

He’s worried about you. He lying, uh, word really? Let’s sort that out. Come on inside. And we can discuss this together

Dan: This image: Of communicating to another person, I see you. I care for you. Comes up again and again.

Thomas Fisher: And. You suspend judgment. Like, I don’t know your struggle. There’s a story early on about somebody who had overdosed from narcotics after a stay in jail, and in so much to that, I’m just like, you know, welcome home. Right. Like I see you,

Thomas Fisher says it’s not an accident that the book is so full of these kinds of expressions of care.

Thomas Fisher: taking care of people, whether or not you’re a doctor or nurse, or many of the other people is ultimately about love. And the book is a love story, and so throughout the book, what I try to capture are the many versions and ways that we love one another because that’s all we got.

Dan: At least it is in the meantime.

Thomas Fisher says several times in our interview: I’m still figuring out what I want to do when I grow up. For now, he’s working in the ER, advising a company that launches new health care companies. Yeah, folks looking for a dollar in health care — and talking about “The Emergency.”

All of the letters in “The Emergency” have the same sign-off: “Onward” — Persisting, and finding ways to express love in the time of… what we’ve got. That is something I’m willing to take with me.

I’ll catch you in three weeks.

Till then, take care of yourself.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg was produced by me, Dan Weissmann, with help from Emily Pisacreta, and edited by Marian Wang. Daisy Rosario is our consulting managing producer.

Adam Raymonda is our audio wizard. Our music is by Dave Winer and Blue Dot Sessions.

Gabrielle Healy is our managing editor for audience. She edits the First Aid Kit Newsletter.

And Bea Bosco is our consulting director of operations.

This season of an arm and a leg is a co production with Kaiser health news. That’s a nonprofit news service about healthcare in America, an editorially-independent program of the Kaiser family foundation.

KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente, the big healthcare outfit. They share an ancestor. The 20th century industrialist Henry J Kaiser.

When he died, he left half his money to the foundation that later created Kaiser health news. You can learn more about him and Kaiser health news at arm and a leg show dot com slash Kaiser.

Diane Webber is national editor for broadcast at Kaiser health news, and Emmarie Hutteman is a correspondent there. They are editorial liaisons to this show.

Also: Our pals at KHN make other podcasts you might like! For instance, if you want The Latest on the politics of health care, you may already follow “What the Health,” hosted by KHN’s chief Washington Correspondent, Julie Rovner. Every week she brings together reporters from top outlets to break down the latest news, including the Supreme Court’s recent bombshell abortion decision. That’s at K H N dot org, slash podcasts.

Thanks to Public Narrative — a Chicago-based group that helps journalists and non-profits tell better stories— for serving as our fiscal sponsor, allowing us to accept tax-exempt donations. You can learn more about Public Narrative at www dot public narrative dot org.

And those donations support this show. If you’re not a donor yet, we’d love to have you. Come on by to www dot arm and a leg show dot com slash support.

Thank you!

Latest Episodes

Our favorite project of 2025 levels up — and you can help

Some more things that didn’t suck in 2025

How to pick health insurance — in the worst year ever

Looking for something specific?

More of our reporting

Starter Packs

Jumping off points: Our best episodes and our best answers to some big questions.

How to wipe out your medical bill with charity care

How do I shop for health insurance?

Help! I’m stuck with a gigantic medical bill.

The prescription drug playbook

Help! Insurance denied my claim.

See All Our Starter Packs

First Aid Kit

Our newsletter about surviving the health care system, financially.